Some Things Are Hard To Say: An Exploration of

Critical Making, Speculative Design, and Reconfiguration.

New connective technologies have had unintended consequences on the meaningfulness of interpersonal communication. In her 2011 book Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, professor Sherry Turkle discusses how current technology is undermining human connection. She proposes that convenience and control are prioritized while diminishing the expectations human beings have of each other (Turkle, p. 1).

In his 2010 Psychology Today article The Effect Of Technology On Relationships, Dr. Alex Lickerman writes that he has “observed people using electronic media to make confrontation easier and have seen more than one relationship falter as a result. People are often uncomfortable with face-to-face confrontation …. In-person interactions, though more difficult, are more likely to result in positive outcomes and provide opportunities for personal growth. Whenever I hear stories of romantic break-ups, firings, or even arguments going on electronically, I cringe. We find ourselves tempted to communicate that way because it feels easier—but the outcome is often worse.”

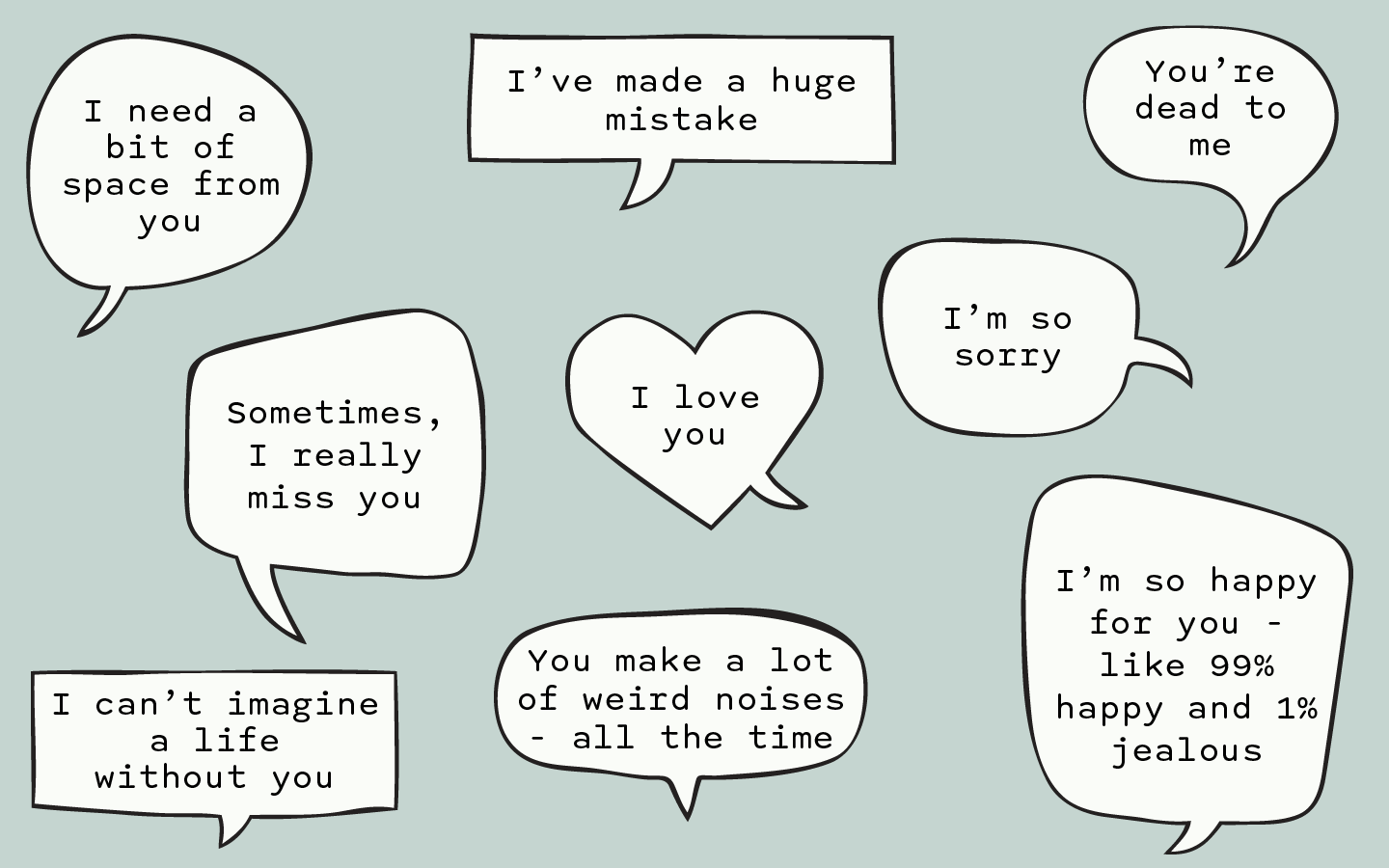

For this project, I imagined a future where machines are our voices and how those machines could be used to vocalize thoughts and emotions that are difficult to express. Since technology is presently utilized as an alternative to in-person communication and because research shows people tend to avoid difficult conversations, this artefact is an exploration of what it would be like to hear something like “I love you” from a convenient touch of a button. Although it is easier to press a button to express a difficult emotion, the intended recipient would not find the experience as meaningful as if the emotion had been expressed directly by the user. Our relationships with others define who we are. How would relationships be reconfigured by a device such as this? I wanted to explore the distributions between humans and non-humans - where the human ends and where a machine begins (Suchman).

This interactive communication artefact is simultaneously humorous and disconcerting and is intended to stimulate discussion and reflection about the ethical and social implications of existing and emerging technologies on interpersonal relationships.

In creating this artefact, I explored the space between creative physical and conceptual exploration which linked conceptual reflection with technical making - also known as Critical Making.

I understand Critical Making to be a form of Design as Inquiry. Design as Inquiry refers to a type of design which produces artefacts for thought rather than for consumption or practical use. This form of design is more “design exploration”, as opposed to “design practice” as it is not driven by commercial interests or practical design problems (Franke). It is an exploration of ideas and possibilities. And as opposed to being focused on the relationship between designer and object, Design as Inquiry centers on creating experimental and hypothetical forms that facilitate the relationships among humans and between humans and artefacts.

As an example of Reconfigurations, Suchman talks about the NRA slogan “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people.” The NRA would have us believe that it is people we should be worrying about. Suchman quotes Bruno LaTour’s book Pandora’s Hope in which he writes “you are different with a gun in your hand and the gun is different with you holding it …the gun is no longer the gun in the drawer and the human is no longer just a human.” Suchman says “when the two are articulated they become someone/something else.” She also states that the agencies - or capacities for action - have increased and have therefore been reconfigured.

Bare Conductive boards

code

presentation

Allen, Chris. “How the Digitalisation of Everything Is Making Us More Lonely.” The Conversation, 2 May 2018, theconversation.com/how-the-digitalisation-of-everything-is-making-us-more-lonely-90870. Accessed 13 May 2018.

Dunne, Anthony. Hertzian Tales: Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience, and Critical Design. The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

Dunne, Anthony, and Fiona Raby. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. The MIT Press, 2013. Digital.

Franke, Björn. Design as a Medium for Inquiry. Fifth Swiss Design Network Symposium, Multiple Ways to Design Research – Research Cases that Reshape the Design Discipline (2009), pp. 225–232

Lickerman, Alex. “The Effect Of Technology On Relationships.” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, 8 June 2010, www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/happiness-in-world/201006/the-effect-technology-relationships.

Malpass, Matthew. Critical Design in Context: History, Theory, and Practices. Bloomsbury Academic, an Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2017. Digital. Kindle Edition.

Ratto, Matt. “Critical Making: Conceptual and Material Studies in Technology and Social Life.” The Information Society, vol. 27, no. 4, 2011, pp. 252–260

Ratto, Matt, et al. “Introduction to the Special Forum on Critical Making as Research Program.” The Information Society, vol. 30, no. 2, 2014, pp. 85–95

SIGCHI, ACM, director. CHI 2010 Lifetime Research Award: Lucy Suchman. YouTube, YouTube, 18 Mar. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=nwHxMWtP_-M.

Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books, 2017.

Suchman, Lucy. Human-Machines Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Wodiczko, Krzysztof. Critical Vehicles: Writings, Projects, Interviews. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1999.